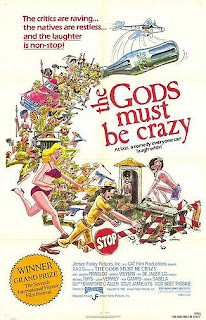

AFED #87: The Gods Must Be Crazy (South Africa/Botswana, 1980); Dir. Jamie Uys

Speak, memory. Back in my last year of university, some thirteen years ago, I found myself spending a lot of time at the student union bar. They were pretty uneventful evenings, truth be told, and most of the time me and few of the other guys on my film studies course used to talk about nothing very much. Actually, they tended to do most the talking, for the main part I was content to listen.

But there used to be a few characters who frequented the place. One of them I particularly recall was an Irish mature student called Rob, who was doing an art degree. Being quite a bit older the guy had a certain swagger and confidence most of us gauche kids lacked (i.e. he'd actually had a life) as well as an occasionally excitable Celtic temperament. He irritated me early on by asking me where I came from - by which he meant ethnically - which, as a hangover of experiencing racism when I was younger was always a bit of a sore point. But he was basically a nice guy and I often wonder what became of him.

Anyway, one evening Rob was talking to us about films and he mentioned The Gods Must Be Crazy.

"It's a great film, you must have seen it, it's very famous."

The what? We looked at one another with quizzical expressions. Despite being supposedly knowledgeable film students we'd never heard of it. What on earth was the mad old git talking about? Rob proceeded to give us an account of the film, something about Africa and Coca Cola bottles, it all sounded a bit strange. That's to say the kind of thing I wanted to check out for myself.

Later I went home and consulted Halliwell's and a couple of my other film guides (this being virtually pre internet) but could find no reference to it. In fact it wasn't until a couple of years later that I finally verified the thing existed at all. Even then it seemed so elusive that I never managed to get hold of a copy and satisfy my curiosity. Until now, that is...

So just what is The Gods Must Be Crazy? Well, it's a knockabout comedy set in South Africa and Botswana that launched a series of films centred around Xi (N!xau), an endearing Sho bushman from the Kalahari desert.

It begins with a mondo style account, complete with voice over - of the bush people's lives and how they're able to survive in this inhospitable environment. The Sho, the film informs us, are completely ignorant of 'civilised' customs and live off the land in an idyllic existence free from such corrupt contrivances as greed or property.

Yet that begins to change when Xi discovers a Coke bottle that's been thrown from a passing airplane. Having never encountered glass before Xi takes it to be a gift from the gods and soon the people of his tribe are putting this remarkable object to a variety of uses.

But because it's so unique the bottle begins to inspire hitherto unknown vices such as jealousy and possessiveness. Dismayed, Xi concludes the bottle is evil and decides there's no alternative but to travel to the end of the world and throw the infernal item off the edge.

After this charming opening the film begins to become a lot more tangled with two more interrelated plot lines. First a band of guerrillas fail in their bid to assassinate the leader of a nearby African country and find themselves fleeing the authorities. We're then introduced to Andrew Steyn, a shy biologist living in outback who has to collect Kate, the attractive new teacher of the local village, in his dodgy Land Rover. There are an interminable series of mirthless slapstick escapades before they get there.

Gradually the elements coalesce and Andrew ends up rescuing Xi from imprisonment when he naively kills a herdsman's goat for food. At the climax the pair help foil the guerrillas when they kidnap Kate's class and Xi is finally able to dispose of the bottle and return home.

The Gods Must Be Crazy can be interpreted in several different ways, none of them strictly right or wrong. On the one hand it makes plenty of use of crude stereotypes: the noble savage with his childlike world view and the comically incompetent black militants. Both are facile and even in 1980 belonged to an earlier time.

Conversely one could say that the white characters don't fare that much better; yet while they're vain and conceited they are at least depicted as educated and articulate. Endemic prejudice remains the proverbial elephant and the makers knew they would be playing to mainly white audiences. Yes, the film may suggest that Xi and his people have the preferable life but in reality they envy our civilised culture as much as we do their 'simpler' one.

Beneath the corpulent excess there's a sweet fable and regardless of the patronising angle N!xau's guileless performance has genuine charm. Told properly this had the potential for an effective epic satire in the tradition of Candide, but it's no better than so so.

But there used to be a few characters who frequented the place. One of them I particularly recall was an Irish mature student called Rob, who was doing an art degree. Being quite a bit older the guy had a certain swagger and confidence most of us gauche kids lacked (i.e. he'd actually had a life) as well as an occasionally excitable Celtic temperament. He irritated me early on by asking me where I came from - by which he meant ethnically - which, as a hangover of experiencing racism when I was younger was always a bit of a sore point. But he was basically a nice guy and I often wonder what became of him.

Anyway, one evening Rob was talking to us about films and he mentioned The Gods Must Be Crazy.

"It's a great film, you must have seen it, it's very famous."

The what? We looked at one another with quizzical expressions. Despite being supposedly knowledgeable film students we'd never heard of it. What on earth was the mad old git talking about? Rob proceeded to give us an account of the film, something about Africa and Coca Cola bottles, it all sounded a bit strange. That's to say the kind of thing I wanted to check out for myself.

Later I went home and consulted Halliwell's and a couple of my other film guides (this being virtually pre internet) but could find no reference to it. In fact it wasn't until a couple of years later that I finally verified the thing existed at all. Even then it seemed so elusive that I never managed to get hold of a copy and satisfy my curiosity. Until now, that is...

So just what is The Gods Must Be Crazy? Well, it's a knockabout comedy set in South Africa and Botswana that launched a series of films centred around Xi (N!xau), an endearing Sho bushman from the Kalahari desert.

It begins with a mondo style account, complete with voice over - of the bush people's lives and how they're able to survive in this inhospitable environment. The Sho, the film informs us, are completely ignorant of 'civilised' customs and live off the land in an idyllic existence free from such corrupt contrivances as greed or property.

Yet that begins to change when Xi discovers a Coke bottle that's been thrown from a passing airplane. Having never encountered glass before Xi takes it to be a gift from the gods and soon the people of his tribe are putting this remarkable object to a variety of uses.

But because it's so unique the bottle begins to inspire hitherto unknown vices such as jealousy and possessiveness. Dismayed, Xi concludes the bottle is evil and decides there's no alternative but to travel to the end of the world and throw the infernal item off the edge.

After this charming opening the film begins to become a lot more tangled with two more interrelated plot lines. First a band of guerrillas fail in their bid to assassinate the leader of a nearby African country and find themselves fleeing the authorities. We're then introduced to Andrew Steyn, a shy biologist living in outback who has to collect Kate, the attractive new teacher of the local village, in his dodgy Land Rover. There are an interminable series of mirthless slapstick escapades before they get there.

Gradually the elements coalesce and Andrew ends up rescuing Xi from imprisonment when he naively kills a herdsman's goat for food. At the climax the pair help foil the guerrillas when they kidnap Kate's class and Xi is finally able to dispose of the bottle and return home.

The Gods Must Be Crazy can be interpreted in several different ways, none of them strictly right or wrong. On the one hand it makes plenty of use of crude stereotypes: the noble savage with his childlike world view and the comically incompetent black militants. Both are facile and even in 1980 belonged to an earlier time.

Conversely one could say that the white characters don't fare that much better; yet while they're vain and conceited they are at least depicted as educated and articulate. Endemic prejudice remains the proverbial elephant and the makers knew they would be playing to mainly white audiences. Yes, the film may suggest that Xi and his people have the preferable life but in reality they envy our civilised culture as much as we do their 'simpler' one.

Beneath the corpulent excess there's a sweet fable and regardless of the patronising angle N!xau's guileless performance has genuine charm. Told properly this had the potential for an effective epic satire in the tradition of Candide, but it's no better than so so.

Comments

Post a Comment